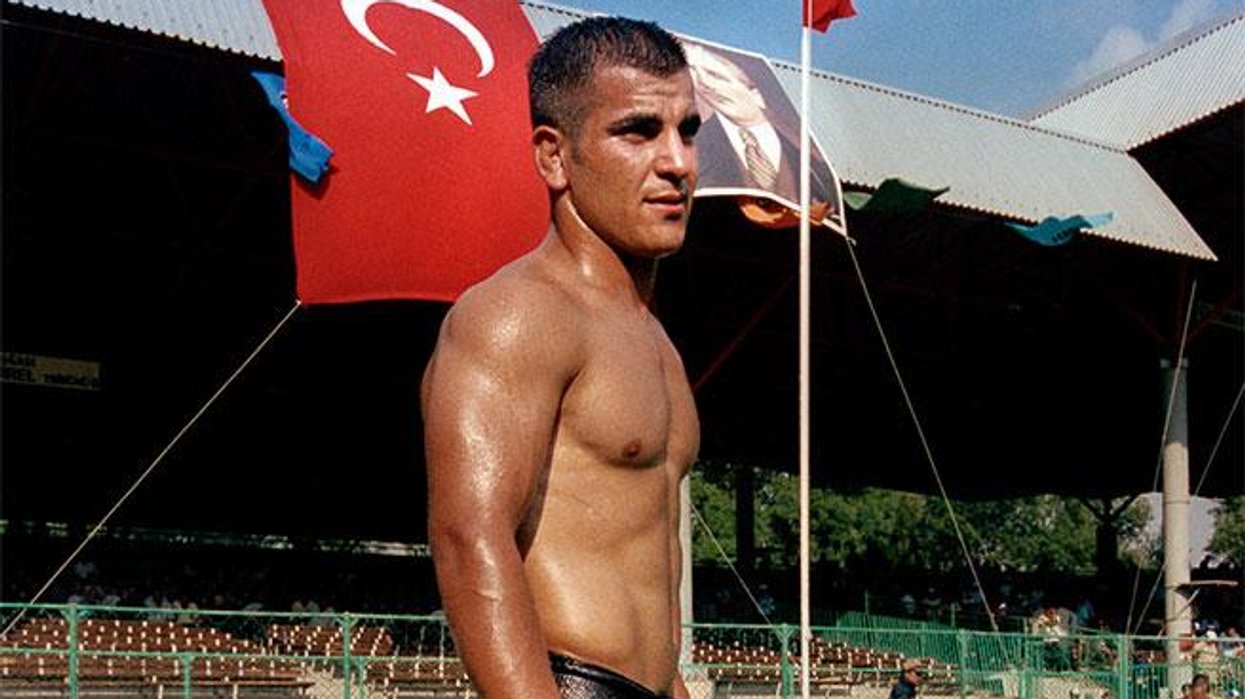

A Cameroonian lesbian seeking asylum in the UK.

No European country has a perfect record on LGBT rights; from Sweden to Slovakia, there’s room for improvement, both in policy and practice. The legislative equality enjoyed throughout the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Spain may be the exception, not the rule, but for now homosexuality is at least legal throughout the European Union. For LGBT asylum-seekers escaping the institutional persecution of regimes like Uganda’s and Iran’s, the relative freedoms of the EU are worth risking everything.

But any hope that the same legal protections offered to EU citizens would be extended to them when they arrive in Europe is often egregiously misplaced. In place of greater freedom, many are greeted with prolonged periods of incarceration. Instead of social acceptance, they are treated with contempt and face discrimination, violence, and sexual abuse in detention centers. Rather than understanding, they’re subjected to drawn-out, sometimes humiliating, decision-making processes designed to establish the “credibility” of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

This systematic failure to protect happens in spite of an EU directive, adopted in 2004, that states unequivocally that those who face persecution for their sexual orientation qualify as refugees. This directive and others are designed to harmonize standards and procedures across Europe, ensuring the fair treatment of LGBT asylum-seekers across the continent. Yet a lack of consistency still pervades the system.

“There’s always been something of a lottery in the EU in that people across the board, any type of asylum-seeker, can face great differences in how their claims are decided. This is also the case with LGBT people,” Paul Dillane says. His charity, U.K. Lesbian and Gay Immigration Group, aids LGBT asylum-seekers with their claims in the United Kingdom and provides them with information, support and legal assistance.

As well as hampering calls for uniformity, the contrasting LGBT-rights landscape across Europe has a significant impact on attitudes toward sexual-minority asylum-seekers. Violence against activists in Serbia, the proposal of propaganda laws similar to Russia’s in Belarus, or the rising antigay rhetoric from ministers in Latvia are unlikely to reassure refugees of a life free from prejudice.

But even in the United Kingdom, ranked first in ILGA-Europe’s Rainbow Map, the treatment of LGBT asylum-seekers is anything but commendable. Despite its reputation as one of the most progressive countries, increasing numbers of LGBT asylum-seekers, upon arrival, are detained indefinitely by the Home Office, the ministerial department responsible for immigration and security.

“We detain more asylum-seekers than any other European country, and unlike other European countries we don’t have a time limit,” Dillane says of the United Kingdom. “If you’re a criminal, and you committed a crime, you know when you’re going to be released, you count down the days. But if you’re a gay asylum-seeker you count up the days — often for weeks and months — because you simply don’t know when you’re going to be released.”

Despite having committed no crime, LGBT asylum-seekers are effectively imprisoned in detention centers, including Yarl’s Wood, where there have been reports of verbal bullying, physical violence, and sexual assault. While they wait for the Home Office to reach a decision in their cases, they are restricted from access to online information that could help their cases. Even the Web site for Dillane’s charity has previously been blocked.

“One of the main problems that LGBT people face in the U.K. and across the region is having to ‘prove’ your sexual orientation or gender identity,” Dillane says. “You’re subjected to a highly accelerated process, and you have a couple of days to prove to the government that you are what you say you are. But there’s no test you can take medical or otherwise to prove you’re gay.”

A detention center in Greece.

Afghan migrants in a detention center on the island of Lesbos.

“We need to see actual improvements in the decision-making process,” he continues. “The fundamental problem is if your asylum claim is wrongly refused, and you’re sent back to a country where your life is at risk — for instance, Uganda, Gambia, or Pakistan — then you can imagine the consequences. So getting the decision right is absolutely essential.”

Even the most well-documented cases are treated with skepticism. Last year, Aderonke Apata, a Nigerian refugee, received the National Diversity Award for her campaign work, challenging the British legal system that penalizes LGBT asylum-seekers. Despite widespread praise for her work, giving evidence in parliament and making it onto

The Independent’s high-profile Rainbow List, the Home Office still refuses to accept she’s lesbian. Apata remains in the asylum process.

Proving or disproving sexual orientation has long been a contentious issue across Europe, but until recently human rights abuses were a frequent part of the “validation” process. Techniques recently employed by immigration officers from various EU states included asking detailed, invasive questions about their sex lives, having them submit video evidence of their homosexual activity, and conducting pseudo-medical tests. A few years ago, Czech authorities even took to strapping electrodes to the genitals of refugees to analyze any physiological reaction to pornography. A much-needed European Court ruling in December prohibited the use of these techniques. It’s the latest in a string of EU directives and rulings designed to guarantee the safety and dignity of LGBT asylum-seekers.

For Katrin Hugendubel, advocacy director at ILGA-Europe, a nongovernmental organization that works for equality and human rights for LGBT people across the continent, patching up the discord between policy and practice is the next step.

“You can have legislation on one side, but if it doesn’t sink in to the people who actually need to conduct these interviews, then it does not make a real difference for people,” Hugendubel says. “We have a good EU framework now to ensure much better treatment of LGBT asylum-seekers in the future, so one thing to really look for now is proper implementation of all the legal requirements regarding sexual orientation and gender identity in asylum procedures. There’s huge work to do with providing information, awareness-raising, sensitivity training, and things like that.”

The European asylum office in Malta is already developing a training module on sexual orientation and gender identity. It may cost time and money, but the European Court alone can’t eradicate the problems; everyone involved in the asylum process — detention center guards, interview translators, and case workers, among others — must have training to better understand the specific situation and requirements of LGBT people.

Encouraging reform in countries that take an ideological stance against introducing pro-LGBT policies is anything but simple. The legislation loses even more credibility when pro-LGBT states like the United Kingdom simply opt out those directives that don’t work for them on a political level.

“In general, the European member states are still struggling with the idea of creating a common asylum system, and there’s still a lot of discrepancy in different member states,” Hugendubel says.

Without a common European-wide policy, one that negates this “asylum lottery,” states will continue to operate unilaterally, and LGBT asylum seekers will continue to face marginalization. In policy at least, the EU offers its own LGBT citizens some of the most comprehensive protections against prejudice. Refusal to unconditionally extend these rights to those who’ve already escaped persecution once is as hypocritical as it is inhumane.