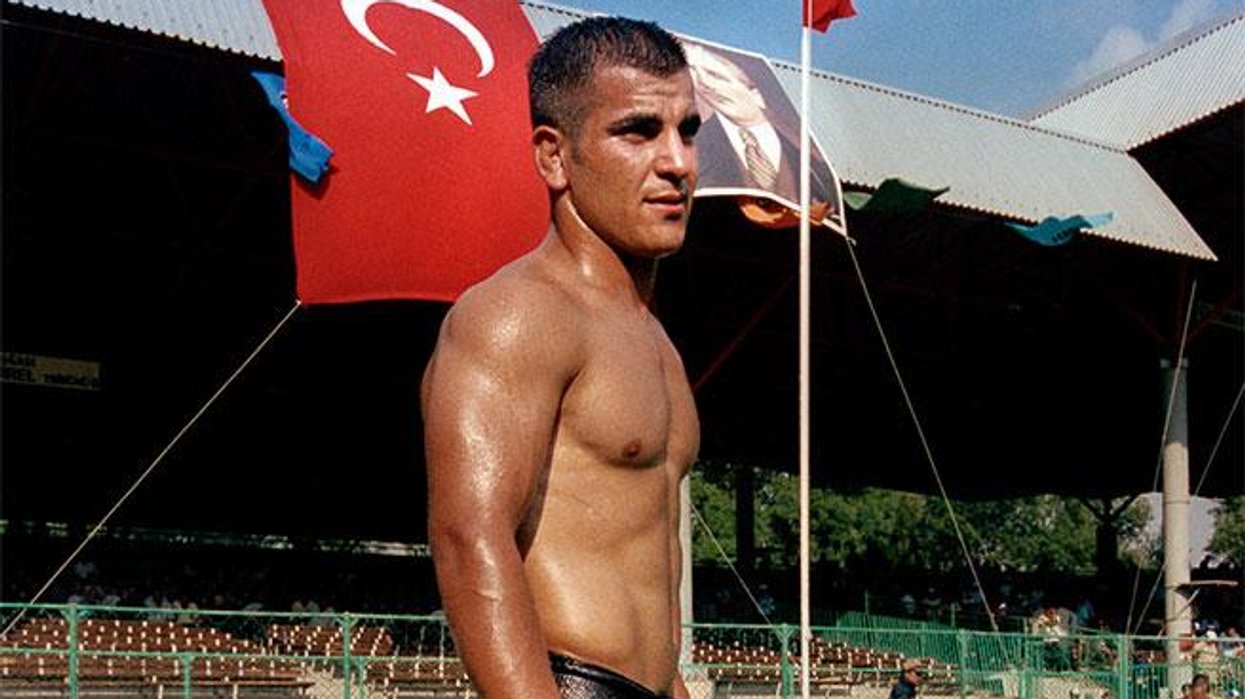

Photo courtesy of A Gay Girl In Damascus: The Amina Profile

In the early weeks of Syria's revolution, international coverage of the widespread conflict was eclipsed by the abduction of a single woman: Amina Abdallah Arraf al Omari. The Syrian-American activists ran the popular blog site A Gay Girl In Damascus, a forum that offered unique insight into both LGBT life in the Middle East and an unfiltered account of the violence directed towards those protesting the Assad regime. When her internet girlfriend, Canadian Sandra Begaria, was told of her arrest, she began a tireless campaign to secure her release, reaching out to the State Department, media outlets like NPR and The Guardian, and individual activists. The only problem, Amina didn't exist. She never had. She was, in fact, the online persona of a straight, middle-aged white man from Georgia.

When the truth of Amina's identity was learned, one of the most high profile and public instances of "catfishing" left Balagria exposed and deeply humiliated. True, their relationship had been carried out solely via textual exhanges, but she hadn't been alone in the belief that Amina was real. The strange saga provided the inspiration for Sophie Deraspe's documentary, A Gay Girl In Damascus: The Amina Profile, which was released in select theaters across the United States last week. However, speaking with Deraspe, it became clear that the story ran much deeper than even she expected.

Out: How did the project come about? How did you get involved with Sandra?

Sophie Deraspe: Actually, I knew Sandra before doing the film. I wouldn't say she was a close friend, but she was in my circle of friends, and I was aware of her meeting with Amina, falling in love with this woman who she had never met. And then when Amina was abducted, and the question was raised about her identity—it really felt as if we were in a thriller. Sandra would share a lot of what was happening. First she was trying to find Amina, to free her, she was working to make sure the media were aware of what was happening, pulling in help from activists from around the world. I really thought, Ok, there is a film going on right now, a thriller. And that's why, in a way, I conducted the film as a thriller. It's how we experienced it.

At what period along this timeline did you actually get involved and start filming? Was it before Amina's identity was discovered?

No. At first, my friend Sandra was so exposed by the media and humiliated in front of the world, so I didn't ask her, "Can I film you and what's happening?" I felt it was too much. But I did tell her, "This is a film, and we're at about the 20-minute mark. More has to come." And I just said it like that, and let the idea sit. And then at the end of 2011, so like 5 months after the real identity behind Amina was revealed, she said she was willing to share all her archives of Amina. She said it was a lot on her shoulders, that she didn't want to have to read them again, but that if I thought there was something to be done, then I should do it. At that time, it wasn't even a question of whether she would be a part of it. Before diving in, though, I asked if she would give me carte blanche, total freedom, in doing the film, because I needed her to trust me. I thought, This is an amazing subject, it says a lot about our contemporary world, about where we get information, but also how we get into relationships. And it says a lot about how we Westerners see the Middle East. And especially being part of the gay community, it feels like everything is bigger, that the idifferences of culture are even bigger.

So she agreed to give me this carte blanche, and that's when I started research. I got to know more about the story and the people involved, and at a certain point I felt, ok—because it wasn't an easy story to tell, it was all happening online, it was really far from moving images and sounds which is the raw material for film—let's have the story told by all the different people who were invovled in it, from different parts of the world. It was at that point that I thought it would be great to have Sandra. I was sure they would be willing to meet with her, because she had been in touch with some of them when trying to free Amina and I knew they'd be interested in meeting her. I also really wanted Sandra to see that she wasn't alone. That there were a lot of people caught in this, bright, educated, well-informed people, just like she is. She's not this naive type of woman who falls into the first trap. So that was how we started.

What was it like meeting these activists? In particular, the Syrian activists.

Yes. We met with an openly gay journalist in Lebanon, and it was amazing to me. He was hiding from the Syrian regime—he was in Lebanon, but he was still threatened there. Yet he was so generous with what he shared of himself. I realized how courageous these people are. They believe in something. So meeting with Danny and the other Syrian who we also met, although in the film I don't say where, raised a broader issue: I didn't know the extent that Syrian people had been impacted by the Amina affair.

Watching the film, you realize that, on the surface, it's a very personal story about Sandra and this relationship. But then as a whole, the film really pays tribute to those brave people actually fighting on the ground. Where do you think the heart of the film lies?

I would say it's really about how we connect with each other. I think that's the key theme of the film. Because all these people were trying to do good—except for the perpetrator, who was quite selfish, I think. But all the others were trying to help, or they were just trying to share in the experience of this young woman who was riskign her life. So this addresses how we get into love affairs, but also how we get informed of what's happening in another culture.

What have some reactions been to the film?

We've had two types of reactions. One from people who empathize a lot with Sandra and what she's been through, her courage in the film, some of whom also have experiences of online cheating. And then there are others who react more to the larger issues,to what's happening in Syria nowadays. They recognize what a shame that story was, because of the sever way the media covered Amina—because she was the type of story that we liked to hear about. It's sad because she's not the truth, and other people were and are just dying in the dark.

When you began this project, did you expect these larger issues to play such a large part of the narrative?

I knew it was going to be a lot about the contemporary world, about sexual identity, the media, how we get into relationships, but what I wasn't expecting was to learn the impact that it had on Syrian people. I thought it was just in Europe and America that all this played out. I didn't know that actual Syrian people had been looking for Amina, that they had exposed themselves to danger. The Amina affair… it hurt a lot of people.

To learn more about screenings, visit The Amina Profile's website. The documentary can also be streamed now via SundanceNow Doc Club.